by Teresa Teo Guttensohn

with contributions from Journeys Pte Ltd

29 July is Global Tiger Day. This article is dedicated to the Malayan Tiger, now extinct in Singapore. It honours the last 200 wild Malayan Tigers fighting for survival in the jungles of Malaysia. Can we save this living emblem of Singapore and Malaysia before it’s too late?

A Powerful Asian Symbol

Throughout history and across many cultures, no animal has inspired as much awe as the largest wild cat on the planet, the majestic Tiger (Panthera tigris).

In Asian art and mythology, this impressive feline is a powerful symbolic animal that is feared, admired and glorified. Unsurprisingly, the endangered tiger is regarded as exotic, charismatic and the most popular animal in the world.

Ancient Chinese Tigers

Our perennial fascination with tigers can be traced back to ancient times. Neolithic rock carvings of tigers going back 10,000 years can be seen in the spectacular cave art of the remote Helan Mountains between the Yinchuan Plains and the Inner Mongolian prairies.

In fact, fossil remains of the oldest ancestral lineage of the tiger (Panthera zdanski) dating more than 2 million years old have been discovered in Gansu, Northwestern China.

Through the Shang, Zhou, Han and successive ruling Chinese dynasties to the Qing era, tiger figures have been carved in jade, cast in bronze and painted on silk and paper.

PHOTO: Journeys Pte Ltd

King of All Forest Animals Consumed

Exalted as ‘Wang’ or King of all forest animals, the tiger (Hu in Mandarin) is a significant feature in Chinese astrology, mythology, religion, art and culture.

However, in the zeal and greed to possess perceived spiritual powers of these formidable predators, tigers continue to be brutally poached and killed — their parts consumed for traditional medicinal purposes in Asia, with hefty demand in China and Vietnam.

A Century of Disappearing Tigers

Our reverence for tigers did not protect them.

Just a century ago in 1910, there were an estimated 100,000 tigers roaming the forests, mangroves, scrublands and grasslands of Asia. They ranged widely from Turkey in the West to China and Russia in the East, from India and the Himalayas to Indochina, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia.

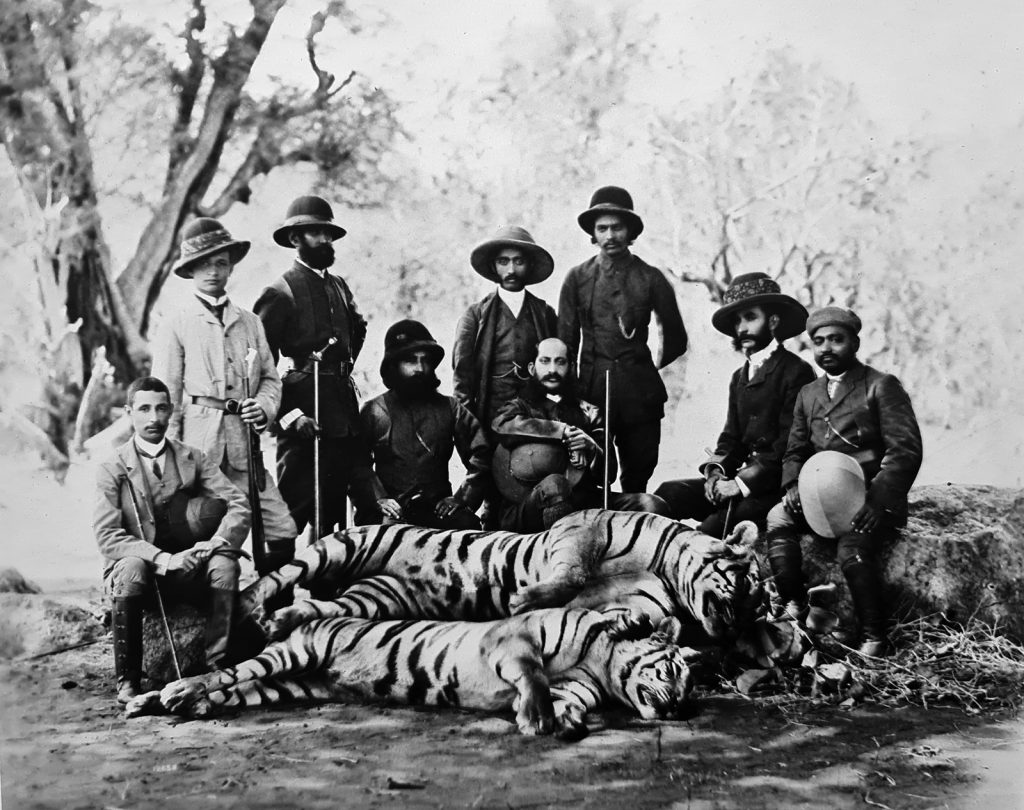

Due to relentless habitat destruction, trophy hunting, illegal wildlife trade, prey depletion and human-wildlife conflict, wild tiger populations have disappeared, and by 2010, tiger numbers plunged shockingly to an estimated 3,200 individuals worldwide.

With concerted tiger conservation programmes in place today, about 3,900 precious wild tigers remain. In some protected parts of Russia, India, Nepal and Bhutan, tiger numbers have increased.

Native Malayan Tiger

The Malayan Tiger (Panthera tigris jacksoni) is a subspecies indigenous to the Malay Peninsula (Southern Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore).

Sadly, like the Sumatran Tiger (Panthera tigris sondaica), Malayan Tigers are dangerously close to extinction. The last remaining 200 critically endangered Malayan Tigers in Peninsular Malaysia are struggling for survival against poaching, habitat destruction and prey loss in Malaysia.

In order to save Malayan Tigers from going the way of the extinct Balinese and Javan tigers, we need to recognise their intrinsic value within natural eco-systems and their profound significance for cultural heritage.

Malayan Tiger Heritage

Malayan Tigers are an indelible part of Singapore’s natural heritage and are inseparable from our island’s history.

A tiger rampant (rearing up on hind legs with forelegs raised) standing on a stalk of padi (“rice” in Malay) appears on the State Crest of Singapore, which was unveiled on 3 December 1959 at the City Hall Chambers, when the island-state became self-governing within the British Empire.

On this national coat of arms, there are not one, but two great felines – a lion stands on the left and a tiger on the right, both supporting a shield emblazoned with a white crescent moon and five stars.

Tiger is More Local

The lion symbolises Singapura, the Lion City, and the tiger represents Singapore’s intertwined history with Malaysia and our tiger heritage. Both noble animals are symbolic of our founding and journey towards independence, and it is sorrowful to imagine a world wiped out of wild tigers and lions.

“The ideas were mine. A lion next to a tiger. Tiger, of course, is a more local animal than the lion.”

Dr Toh Chin Chye (then Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister), in an oral interview with the National Archives of Singapore on conceiving the state crest in 1959.

Harimau – A Traditional Malay Symbol

The Harimau (tiger in Malay) or Pak Belang (meaning “Sir Stripes”) is a traditional Malay symbol of strength, bravery and power.

The tiger is the chosen national animal of Malaysia and is depicted on the heraldry of many Malaysian institutions. The stealth and ferocity of tigers is expressed in the Malay idioms “tunjuk belang” meaning to show stripes, or “sembunyi kuku” which means “hidden claws”.

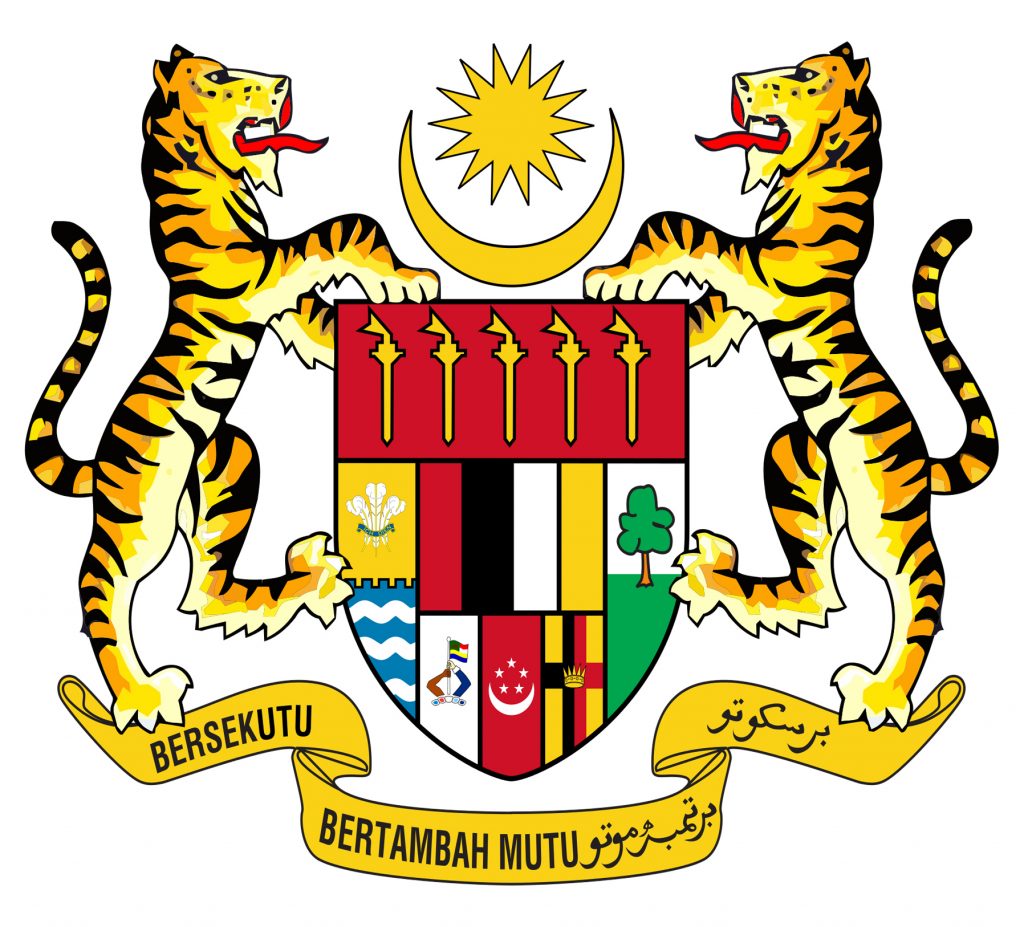

The Federation of Malaysia coat of arms, used between 1963 to 1965, included three the new member states of Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore. It features two amber tigers guarding a shield, with Singapore represented by white stars and a crescent moon on a red background.

This historical coat of arms is a reminder of when Singapore was one of the fourteen states of Malaysia, which marked the end of 144 years of British rule in Singapore.

Coat of Arms with Two Tigers

In the current national coat of arms of Malaysia (Jata Negara in Malay), used since 1988, two formidable fiery-orange and black-striped tigers support a shield which features, among other symbols, a Pinang or Betel-nut Palm (Areca catechu) and a Malacca Tree (Phyllanthus emblica).

Birthplace of Tiger Beer

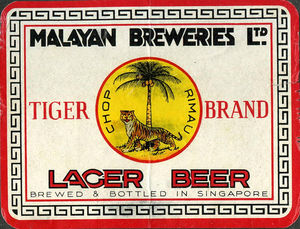

Mention tigers in Singapore to any local or tourist, and two heritage brands instantly leap into mind – Tiger Beer and Tiger Balm.

Singapore’s first local brew, Tiger Beer, was concocted in 1932 by Malayan Breweries Limited. First marketed as a healthy beverage for all, it has since gone on to quench the thirst of many in Asia and around the world.

The 1956 book title “Time for a Tiger”, the first part of “The Malayan Trilogy” on post-war Malaya by Anthony Burgess, was borrowed from the slogan of his favourite beer.

Recognising that tigers are more than just a brand icon, and that tigers have deep cultural meaning in Asia, Tiger Beer is helping to save endangered wild tigers by donating and embarking on a long-term global partnership with World Wide Fund for Nature to support tiger conservation efforts.

Home of Tiger Balm

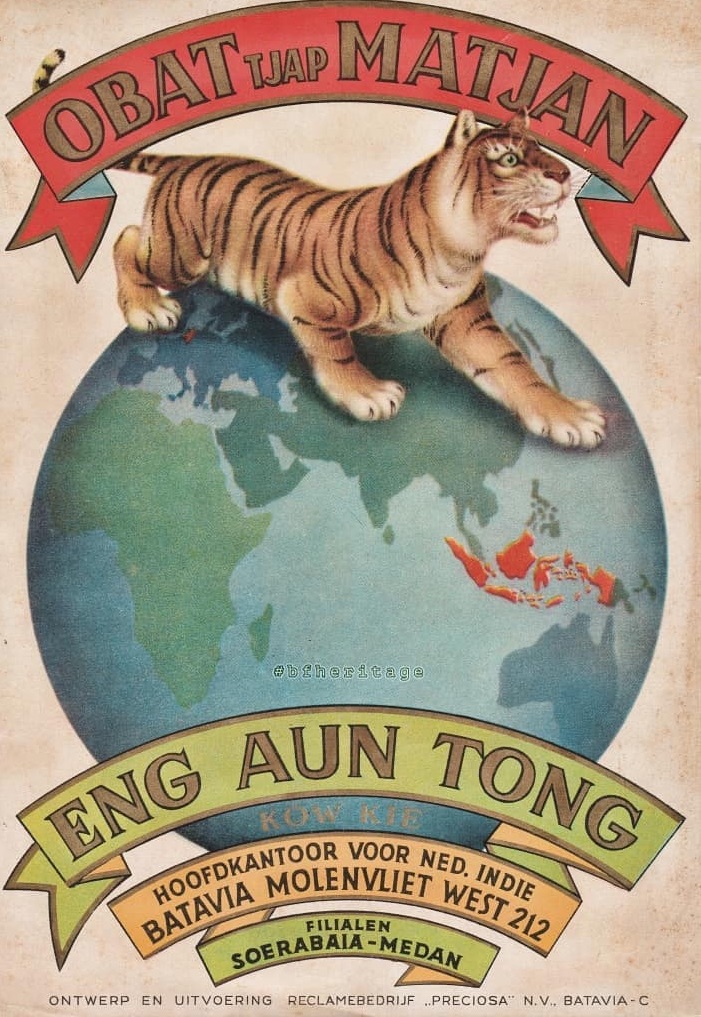

The fascinating story of Tiger Balm in Singapore starts with Aw Boon Haw (meaning ‘Cultured Tiger’ in Hokkien) and Aw Boon Par (‘Cultured Leopard’), who were ethnic Chinese born in Rangoon, British Burma, in the late 19th century.

Boon Haw and Boon Par moved to Singapore in the 1920s to establish a headquarters for Tiger Balm, transforming their late father’s humble medicinal hall into a million-dollar business empire centred around an internationally-renowned brand, Tiger Balm.

Fortunately, this traditional analgesic ointment does not contain any actual tiger parts and was simply named after the Cultured Tiger himself.

An Art Deco Haw Par Villa

The caring Boon Haw decided to build a palatial villa and garden for his homesick younger brother Boon Par. Considered a crazy-rich Asian and millionaire philanthropist of his era, he settled on a hilly area on Singapore’s West Coast, along Pasir Panjang Road, which had good ‘feng shui’.

Boon Par was English-educated, but Boon Haw wanted to pay tribute to their Chinese roots, so the result was a marriage of East and West. The luxurious Art Deco style building was named Haw Par Villa (an amalgamation of the brothers’ names). Together with a large surrounding garden, it was completed by 1937. This was one year after the Haw Par Mansion was built in Hong Kong in 1936.

A Quirky Tiger Balm Garden

This enormous garden, sprawling over eight acres, is replete with statues and dioramas of Chinese culture and heritage. Throughout the park, the stamp of the tiger is clear. The villa has bronze panels of tigers set in doorways. And all around the garden, tiger statues and carvings abound.

Little did the Aw brothers imagine that their eclectic park would later become a historic site and cultural landmark in a fast-moving and ever-changing world. A quirky yet enlightening treasure trove of Asian culture, history, philosophy and religion, it is Singapore’s largest outdoor gallery and the last of its kind in the world.

Tiger Cars with A Roar

To promote Tiger Balm, Boon Haw came up with creative marketing ideas that were almost unheard of in his time. One such tactic was converting his stable of cars into ‘Tiger Cars’, which attracted plenty of attention wherever he went, and typified his flair in promoting his business. His aggressive marketing all over China and Southeast Asia succeeded in springing Tiger Balm to household name status.

The first Tiger Car was a 1927 German NSU, and the second was a 1932 Humber with the auspicious licence plate number ‘8989’. Each car was painted with tiger stripes, a tiger head with whiskers and fangs covering the radiator, red bulbs for the tiger’s eyes, and even the sound of the horn resembled a tiger’s roar.

In the wild, a tiger’s roar can be heard as far as 3km away. In Singapore, this is akin to hollering from Fullerton Hotel and being heard at Raffles Hotel miles away!

Time for Tigers is Running Out – ACT NOW!

Since time immemorial, the awesome tiger has fired our imagination with its strength, courage, prowess and beauty. It has filled our art, stories, literature and mundane lives with its majesty. At the same time, it has been ruthlessly exploited and hunted to the brink of extinction.

Tragically, the last wild Malayan Tiger in Singapore was shot to local extinction 90 years ago on 26 Oct 1930 by Mr Ong Kim Hong and members of the Straits Hunting party in the jungles near the 16th milestone of Choa Chu Kang village. Hopefully, this will not be the eventual fate of the last surviving 200 wild Malayan Tigers.

As powerful and mighty as they seem, tigers are helpless against the most destructive species of all – Homo sapiens. According to a landmark United Nations (UN) IPBES 2019 Report*, tigers and one million other animal and plant species are threatened with extinction, thanks to human activities.

According to the leaders of UN, WHO and WWF International, pandemics like COVID-19 are a direct result of destruction of nature.** The fraying of the web of life constitutes a direct threat to human well-being. Saving tigers, stemming species biodiversity loss and protecting essential eco-systems means saving ourselves.

Heed the Cry of the Tiger!

Time for the iconic tiger is seriously running out. Can we not hear and heed the anguished cries of the beleaguered Malayan Tiger?

We surely have the means, but do we have the will to save this living emblem of Singapore and Malaysia before it is gone from the last remaining wilderness? With forest habitats shrinking and extinction looming, the time to ACT and save tigers is NOW or never!

How you can help to Save the Malayan Tiger: Donate to MYCAT to support their Malayan Tiger conservation efforts, or join a CAT Walk: going on an anti-poaching, anti-deforestation guided walk in critical tiger habitat. For more details, visit mycat.my

How to join Haw Par Villa Tours:

Find out for yourself the fascinating stories behind the 1,000 sculptures and dioramas by going on the “Finding Your Tao” day tour which brings you on a journey through the tremendous riches and the eventual tragic downfall of the Aw brothers. Alternatively, join the “Journeys to Hell” twilight tour which reveals the mysterious side of Haw Par Villa.

Due to current COVID-19 restrictions, pre-registration is required for tours. Call +(65) 6773 0103 (Mon-Fri 9am to 6pm) or email: hpv@journeys.com.sg to check on availability. For more details, please visit www.hawparvilla.sg

Acknowledgements

With many thanks to Journeys Pte Ltd, MYCAT and Marcus Chua for photos and contributions.

References

*UN Report: Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’; Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating’ – United Nations Sustainable Development - Read More

**The Guardian (theguardian.com) - Read More

Haw Par Villa (hawparvilla.sg) Malaysian Conservation Alliance for Tigers (mycat.my) Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum (lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg) • Ecology Asia (ecologyasia.com) • Singapore Wildcat Action Group (swagcatsg.wixsite.com/mysite) • Nature Society, Singapore (nss.org.sg) • World Wide Fund for Nature (wwf.sg) • National Geographic (nationalgeographic.com) • World Health Organisation (who.int) • United Nations (un.org) • The Guardian (theguardian.com) • EcoWatch (ecowatch.com) • PLOS ONE (journals.plos.org) • Live Science (livescience.com) • Tiger Beer (tigerbeer.com.sg) • National Library Board - Biblioasia (nlb.gov.sg) • National Archives of Singapore (nas.gov.sg) • National Gallery, Singapore (nationalgallery.sg) • Raffles Hotel (rafflessingapore.com) • The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (metmuseum.org) • Bradshaw Foundation (bradshawfoundation.com) • Ministry of Culture Community and Youth, Singapore (mccy.gov.sg) • Coat of Arms Singapore – Wikipedia (en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/coat_of_arms_of_singapore) • Malaysia Coat of Arms (malaysia.gov.my/portal/content/137?language=my) • Armorial of Malaysia- Wikipedia (en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/armorial_of_malaysia) • The Patriots (thepatriots.asia/harimau-dan-masyarakat-melayu/)

Publications:

Majestic Stripes, The Malayan Tiger, Malayan Banking Berhad, 2010

Wild Animals of Singapore, Vertebrate Study Group, NSS, Draco Publishing, Nick Baker and Kelvin Lim, 2008

The Singapore Red Data Book: Threatened Plants and Animals of Singapore, Nature Society Singapore, PKL Ng and YC Wee, 1994

The Singapore Red Data Book: Threatened Plants and Animals of Singapore (Second Edition), Nature Society Singapore, GWH Davidson, PKL Ng and Ho Hua Chew

Malay Annals (translated from the Malay Language), Longman/Hurst/Rees/Orme/Brown, John Leyden, 1821

The Malay Archipelago, Periplus Editions, Alfred Russel Wallace, 1869

Malaysia and Singapore in Pictures, Sterling Publishing Co, Inc, New York, James Nach, 1969

The First 150 Years of Singapore, Donald Moore Press Limited, Singapore, Donald and Joanna Moore, 1969

Singapore, A Pictorial History 1819-2000, Archipelago Press, Gretchen Liu, 1999

Seven Hundred Years – A History of Singapore, National Library Board, Singapore, 2019

The Chinese Spirit Road: The Classical Tradition of Stone Tomb Statuary, Yale University Press, Ann Paludan, 1991

Princely India, Clark Warswick, Arginde/Pennwick/Knopf, New York, 1980